| Irish Forums Message Discussion :: O'Hare World War II Flying Ace |

| Irish Forums :: The Irish Message

Forums About Ireland and the Irish Community, For the Irish home and Abroad. Forums include- Irish Music, Irish History, The Irish Diaspora, Irish Culture, Irish Sports, Astrology, Mystic, Irish Ancestry, Genealogy, Irish Travel, Irish Reunited and Craic

|

|

O'Hare World War II Flying Ace

|

|

|

| Irish

Author |

O'Hare World War II Flying Ace Sceala Irish Craic Forum Irish Message |

jodonnell

Sceala Philosopher

Location: NYC

|

| Sceala Irish Craic Forum Discussion:

O'Hare World War II Flying Ace

|

|

|

On this day February 20, 1942

Pilot O'Hare becomes first American WWII flying ace

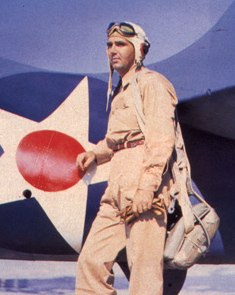

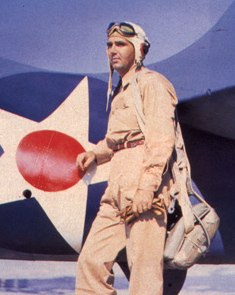

On this day, Lt. Edward O'Hare takes off from the aircraft carrier Lexington in a raid against the Japanese position at Rabaul-and minutes later becomes America's first flying ace.

In mid-February 1942, the Lexington sailed into the Coral Sea. Rabaul, a town at the very tip of New Britain, one of the islands that comprised the Bismarck Archipelago, had been invaded in January by the Japanese and transformed into a stronghold--in fact, one huge airbase. The Japanese were now in prime striking position for the Solomon Islands, next on the agenda for expanding their ever-growing Pacific empire. The Lexington's mission was to destabilize the Japanese position on Rabaul with a bombing raid.

Aboard the Lexington was U.S. Navy fighter pilot Lt. Edward O'Hare, attached to Fighting Squadron 3 when the United States entered the war. As the Lexington left Bougainville, the largest of the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific [and still free from Japanese control], for Rabaul, ship radar picked up Japanese bombers headed straight for the carrier. O'Hare and his team went into action, piloting F4F Wildcats. In a mere four minutes, O'Hare shot down five Japanese G4M1 Betty bombers--bringing a swift end to the Japanese attack and earning O'Hare the designation "ace" [given to any pilot who had five or more downed enemy planes to his credit].

Medal of Honor presentation on 21 April 1942: President Roosevelt, Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy [behind FDR], Admiral Ernest King, Edward O'Hare and his wife Rita.

Although the Lexington blew back the Japanese bombers, the element of surprise was gone, and the attempt to raid Rabaul was aborted for the time being. O'Hare was awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery--and excellent aim.

Accolades

On 26 March Butch was greeted at Pearl Harbor by a horde of reporters and radio announcers. During a radio broadcast in Honolulu, he enjoyed the opportunity to say hello to Rita ["Here's a great big radio hug, the best I can do under the circumstances"] and to his mother ["Love from me to you"]. On 8 April he thanked the Grumman Aircraft Corporation plant at Bethpage [where the F4F Wildcat was made] for 1,150 cartons of Lucky Strike cigarettes, a grand total of 230,000 smokes. Ecstatic Grumman workers had passed the hat to buy the cigarettes in appreciation of O'Hare's combat victories in one of their F4F Wildcats. A loyal Camel smoker, Butch opened a carton, deciding, that it was the least he could do for the good people back in Bethpage. In his letter to the Grumman employees he wrote, "You build them, we'll fly them and between us, we can't be beaten." It was a sentiment he would voice often in the following two months.

By shooting down five bombers O'Hare became a flying ace, was promoted to Lieutenant Commander, and became the first naval aviator to be awarded the Medal of Honor. With President Franklin D. Roosevelt looking on, O'Hare's wife Rita placed the Medal around his neck. After receiving the Medal of Honor from Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lt. O'Hare was described as "modest, inarticulate, humorous, terribly nice and more than a little embarrassed by the whole thing".

Official Citation

"For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in aerial combat, at grave risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty, as section leader and pilot of Fighting Squadron 3 on 20 February 1942. Having lost the assistance of his teammates, Lt. O'Hare interposed his fighter between his ship and an advancing enemy formation of 9 attacking twin-engine heavy bombers. Without hesitation, alone and unaided, he repeatedly attacked this enemy formation, at close range in the face of intense combined machine gun and cannon fire. Despite this concentrated opposition, Lt. O'Hare, by his gallant and courageous action, his extremely skillful marksmanship in making the most of every shot of his limited amount of ammunition, shot down 5 enemy bombers and severely damaged a sixth before they reached the bomb release point. As a result of his gallant action--one of the most daring, if not the most daring, single action in the history of combat aviation--he undoubtedly saved his carrier from serious damage."

O'Hare received further decorations later in 1943[15] for actions in battles near Marcus Island in August and subsequent missions near Wake Island in October.

Mission into Darkness

Faced with U.S. daylight air superiority, the Japanese quickly developed tactics to send torpedo-armed Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers on night missions from their bases in the Marianas against the U.S. aircraft carriers. In late November they launched these low-altitude strikes almost nightly to get at Enterprise and other American ships, so Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford, O'Hare and Commander Tom Hamilton, CV-6 Air Officer, were deeply involved in developing ad hoc counter-tactics, the first carrier-based night fighter operations of the U.S. Navy. O'Hare's plan required the Carrier's Fighter Director Officer [FDO] to spot incoming enemy formations at a distance and send a "Bat Team" section consisting of a TBF Avenger torpedo bomber and two F6F Hellcat fighters toward the Japanese intruders. Although improvements in new types of aviation radar were soon forthcoming from the engineers at MIT and the electronic industry, the available primitive radars in 1943 were very bulky, attributed to the fact that they contained vacuum tube technology. Radars were carried only on the roomy TBF Avengers, but not on the smaller and faster Hellcats, so the radar-equipped TBF Avenger would lead the Hellcats into position behind the incoming bombers, close enough for the F6F pilots to spot visually the blue exhaust flames of the Japanese bombers. Finally, the Hellcats would close in and shoot down the torpedo-carrying bombers.

One of the four 'Bat Team' fighter pilots to conduct this experimental night fighter operations to intercept and destroy enemy bombers attacking Allied landing forces was Lt. Roy Marlin Voris, who later founded the Navy's flight demonstration squadron, the Blue Angels.

On the night of 26 November 1943, the Enterprise introduced the experiment in the co-operative control of Avengers and Hellcats for night fighting, when the three-plane team from the ship broke up a large group of land-based bombers attacking Task Group TG 50.2. O'Hare volunteered to lead this mission to conduct the first-ever Navy nighttime fighter attack from an aircraft carrier to intercept a large force of enemy torpedo bombers. When the call came to man the fighters, Butch O'Hare was eating. He grabbed up part of his supper in his fist and started running for the ready room. He was dressed in loose marine coveralls. The night fighter unit consisting of 1 VT and 2 VF was catapulted between 1758 and 1801. The pilots for this flight were Butch O'Hare and Ensign Warren Andrew "Andy" Skon of VF-2 in F6Fs and the Squadron Commander of VT-6, LCMDR. John C. Phillips in a TBF1-C. The crew of the TBF torpedo plane consisted on Lt.[jg] Hazen B. Rand, a radar specialist and Alvin Kernan, A. B., AOM1/c. The 'Black Panthers', as the night fighters were dubbed, took off before dusk and flew out into the incoming mass of Japanese planes.

Confusion and complications endangered the success of the mission. The Hellcats first had trouble finding the Avenger, the FDO had difficulty guiding any of them on the targets. O'Hare and Ensign W. Skon in their F6F Hellcats finally got into position behind the Avenger. Butch O'Hare had been well aware of the deadly danger of friendly fire in this situation - he radioed to the Avenger Pilot of his section, "Hey, Phil, turn those running lights on. I want to be sure it's a yellow devil I'm drilling."

O'Hare was last seen at the 5 o'clock position of the TBF. About that time, the turret gunner of the TBF, Alvin Kernan [AOM1/c] noticed a Japanese G4M Betty bomber above and almost directly behind O'Hare's 6 o'clock position. Kernan opened fire with the TBF's .50-cal. machine gun in the dorsal turret and a Japanese gunner fired back. Butch O'Hare's F6F Hellcat apparently was caught in a crossfire. Seconds later Butch's F6F slid out of formation to port, pushing slightly ahead at about 160 knots and then vanished in the dark. The Avenger pilot, Lieutenant Commander Phillips, called repeatedly to O'Hare but received no reply. Ensign Skon responded: "Mr. Phillips, this is Skon. I saw Mr. O'Hare's lights go out and, at the same instant, he seemed to veer off and slant down into darkness." Phillips later asserted, as the Hellcat dropped out of view, it seemed to release something drop almost vertically at a speed too slow for anything but a parachute. Then something "whitish-gray" appeared below, perhaps the splash of the aircraft plunging into the sea.

Lieutenant Commander Phillips reported the position (1°26' north latitude, 171°56' east longitude) to the ship. After dawn a three-plane search was made, but no trace of O'Hare or his aircraft was found. On November 29 a PBY Catalina flying boat also conducted a search with no positive result, and O'Hare was reported missing in action.

For 54 years there was no definitive answer as to whether he had been brought down by friendly fire or the Japanese bomber's nose gunner. In 1997 the publication of the primary source for this article, Fateful Rendezvous: The Life of Butch O'Hare, by Steve Ewing and John B. Lundstrom (see References below) shed new light. Ewing and Lundstrom very clearly state, more than once, that Japanese guns, and not Kernan's, killed Butch O'Hare.

In Chapter 16, "What Happened to Butch," the authors write, "Butch fell to his old familiar adversary, a Betty. Most likely he died from, or was immediately disabled by, a lucky shot from the forward observer crouched in the rikko's [Betty's] forward glassed-in nose...the nose gunner's 7.7mm slugs very likely penetrated Butch's cockpit from above on the port side and ahead of the F6F's armor plate."[32] In the Index, Ewing and Lundstrom flatly state that Kernan is "wrongly accused of shooting down Butch."

Why the confusion for so many years? Ewing and Lundstrom point out that the "most influential and oft-cited" account of O'Hare's last mission came in a 1962 history of the Enterprise by CDR Edward P. Stafford, which relied on action reports and recollections of former Enterprise crew, but did not contain interviews with any of the living participants. By contrast, Ewing and Lundstrom came to their conclusions on what happened to Butch after interviewing the still living survivors of O’Hare’s last mission: F6F pilot Skon, TBF radar officer Rand, and TBF gunner Kernan. Ewing and Lundstrom write, "Through Stafford and other accounts based largely on the action reports, Butch has wrongly become known as one of America's most famous "friendly fire" casualties."

On 9 December, official word arrived that O'Hare was missing in action. His mother Selma left for San Diego to be with his wife Rita and his daughter Kathleen. Lt. Cmdr. Bob Jackson wrote Rita O'Hare from the Enterprise to describe the extensive but unsuccessful search for her husband. In the letter, Lt. Cmdr. Jackson quoted Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford saying of Butch O'Hare that he "never saw one individual so universally liked." The hardest thing O'Hare's former wingman Lt. Alex Vraciu had to do was to talk to O'Hare's wife Rita after returning stateside. On 20 December 1943, a Solemn Pontifical Mass of Requiem was offered for Butch O'Hare at the St. Louis Cathedral.

As O'Hare went missing on 26 November 1943, and was declared dead a year later, his widow Rita received her husband's posthumous decorations, a Purple Heart and the Navy Cross on 26 November 1944.

In 1945 the U.S. Navy destroyer USS O'Hare [DD-889] was named in O'Hare's honor. As a tribute to Butch O'Hare, on 19 September 1949, the Chicago-area Orchard Depot Airport was renamed O'Hare International Airport. The same month, O'Hare's name was engraved on the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific "Wall of the Missing" in Honolulu. In March 1963, President John F. Kennedy did a wreath-laying ceremony at O'Hare Airport to honor Butch O'Hare. The Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum is honoring O'Hare with a F4F-3A on display and a plaque dedicated by the USS Yorktown CV-10 association, "May Butch O'Hare rest in peace..."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|