| Irish Forums Message Discussion :: Dubin 1911 archives and census - genealogy resource |

| Irish Forums :: The Irish Message

Forums About Ireland and the Irish Community, For the Irish home and Abroad. Forums include- Irish Music, Irish History, The Irish Diaspora, Irish Culture, Irish Sports, Astrology, Mystic, Irish Ancestry, Genealogy, Irish Travel, Irish Reunited and Craic

|

|

Dubin 1911 archives and census - genealogy resource

|

|

|

| Irish

Author |

Dubin 1911 archives and census - genealogy resource Sceala Irish Craic Forum Irish Message |

Irish News

|

| Sceala Irish Craic Forum Discussion:

Dubin 1911 archives and census - genealogy resource

|

|

|

Sources from

The household returns and ancillary records for the censuses of Ireland of 1901 and 1911, which are in the custody of the National Archives of Ireland, represent an extremely valuable part of the Irish national heritage.

The household returns and ancillary records for the censuses of Ireland of 1901 and 1911, which are in the custody of the National Archives of Ireland, represent an extremely valuable part of the Irish national heritage.

search the census and find your Dublin ancestor from 1911

What was Dublin like in 1911

Dublin, in 1911, was a mass of contradictions. A second city of the British Empire, Dublin was also the first city of nationalist Ireland and, within its boundaries, the divisions of class and culture were extraordinary. This was a city of genuine diversity, its many complexities defying easy explanations. Rich and poor, read more -

Sinead Crowley, RTE Arts & Media Correspondent, reports on the launch of nationalarchives which collates information from the 1911 Census relating to Dublin initially, and nationally by the end of 2008Irish Forums Members Only Article:If you are a logged in Irish Forums member but still cannot view, then: You do not have adequate posts to see the content. This content is for active Irish Forum members that have made at least 10 posts.

What was Dublin like in 1911

Dublin, in 1911, was a mass of contradictions. A second city of the British Empire, Dublin was also the first city of nationalist Ireland and, within its boundaries, the divisions of class and culture were extraordinary. This was a city of genuine diversity, its many complexities defying easy explanations. Rich and poor,

immigrant and native, nationalist and unionist, Catholic, Protestant, Jew and Quaker, and so many more, were all bound together in the life of the city.

In 1911 Dublin was moving into a decade of remarkable change; little would remain untouched. First, the 1913 Lockout redefined the nature of commerce and class relations in the city. The 1916 Rising, followed by the 1919-21 War of Independence and the ensuing civil war, turned politics and government on its head. Not all change was driven by local events. World War One saw many thousands of Dubliners fight in the trenches of Gallipoli, Flanders and the Somme. Many never came home. Those who did were often radically transformed, partly by the war and partly by what had happened at home while they were away.

OTHER IRISH GENEALOGY RESOURCES

All about the Irish genealogy online Ireland ancestry census

The iconic streets of Bloomsday (16 June 1904, the date on which James Joyce set Ulysses and Leopold Bloom’s epic tour of Dublin) were already being lost. The city was changing as the suburbs grew in scale and importance. Nothing transformed the physical appearance of Dublin as profoundly as the evolution in transport. Trams, horses and bicycles still dominated transport in Dublin but the private motor car was growing in importance.

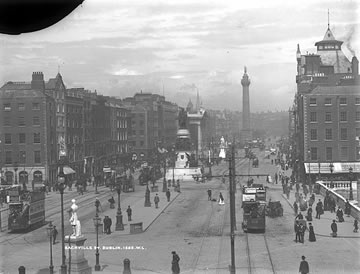

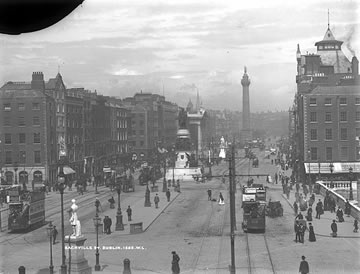

Sacville Street

Sackville Street c.1890-1910. It was here that John Redmond unveiled a monument to Charles Stewart Parnell in October 1911.

(NLI: LROY 1662 )

Dublin was also a port city, though not in the manner of Belfast, Liverpool or Glasgow. On 1 April 1911 the Titanic was launched from the Harland and Wolff Shipyards in Belfast; no project of this scale could be undertaken in Dublin. There was no major ship-building industry, no vast industrial sector, no sense of a place driven by the impulses of manufacturing entrepreneurs and their workforce.

There was, of course, industry and innovation,, like Sir Howard Grubb’s telescope-making factory at Observatory Lane in Rathmines, but never on the scale of comparable cities in other parts of the United Kingdom of grate britain and Ireland. Administration and commerce, rather than industry, were what drove the city’s economy. Dublin port was more a transit point for British goods imported to Ireland and for the agricultural export trade of the city’s rural hinterland, not least the cattle boats that left at least seven times a day, as part of the eighty weekly sailings to England.

A tenement room

Urban living: A dilapidated tenement room in the Coombe area in 1913.

(RSAI, DD, No.83)

Alongside the cattle on many of those boats were emigrants leaving a country unable to offer even the possibilities of a basic existence. Some were Dubliners, many were from the Irish countryside and were merely passing through the city, certain in the knowledge that there was simply no work available to them. Behind them they left the brutal reality of daily life for tens of thousands who lived in tenement slums, starved into ill-health, begging on the fringes of society. In parts, Dublin was incredibly poor. A notoriously high death-rate was attributable, at least in part, to the fact that 33% of all families lived in one-roomed accommodation. The slums of Dublin were the worst in the United Kingdom, dark, disease-ridden and largely ignored by those who prospered in other parts of the city.

Even for those with work, life was precarious. Trade unions attempted to organise against the backdrop of low wages and chronic over-supply of labour. On 27 May 1911 James Larkin first published The Irish Worker, the paper of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, which had enlisted 18,000 men into its ranks in just two years.

On 27 May 1911 Jim Larkin, first published The Irish Worker, the paper of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (NLI)

Labour was growing increasingly militant, but its opponents were powerful and equally determined to resist change. William Martin Murphy founded the Dublin Employers’ Federation on 30 June. Murphy owned railways, tramways, Clery’s Department Store and, critically, the Irish Independent. The power of the employers was obvious as two major strikes during 1911, one by bakers, the other by railway workers, ended in abject defeat. As the Dublin economy continued to stagnate, strikes followed one after the next, and the greatest labour dispute in Irish history, the 1913 Lockout, was just around the corner.

A well-dressed crowd attend the Great Exhibition, Herbert Park, 1907.

Dublin politics were not often about poverty, however. Of increasing political importance were the expanding Catholic middle classes, gaining steady prominence in the city’s professional and administrative ranks. Throughout the nineteenth century, power in Dublin slowly shifted from the Protestant ascendancy to an emerging Catholic elite, who were apparently nationalist in aspect. This nationalism, however, was ambiguous in its politics and in its culture.

As the centre for British rule in Ireland for eight centuries, Dublin was the focal point of the substance and symbols of British culture. This culture – its literature, its newspapers, its sports, its music, its entertainment – was adopted with little modification by many amongst the middle classes, eager for advancement, unashamed by pursuit of prosperity.

Dublin was home to Patrick Pearse, whose work as a writer and educationalist was central to the Gaelic revival of the early 20th century.

(NLI, 'Political and Famous Figures,' Box VI)

In opposition to this, a resurgent nationalist culture was asserting itself uncertainly. Based on the premises (or perceived premises) of peasant life and traditions, revival of the Irish language, Irish dress, Irish music and Irish games, this was a resurgence which did not play easily with urban life. Dublin could not be easily accommodated in any vision which idealised rural life. And yet, Dublin lay at the heart of this Gaelic revival, home to Patrick Pearse and many of the writers, educationalists and intellectuals who recast the idea of Ireland as a sovereign Gaelic nation, free from the control of its imperial master.

Their vision was often rural, but it was not provincial. The revivalists were acutely aware of what was happening beyond Irish shores, in Europe and in North America. All told, culture in the city was profoundly modern, even an inspiration for modernism. This was the city where James Joyce and William Butler Yeats had lived and worked, and where Samuel Beckett, 5 years old in 1911, would later study. Yeats, indeed, would continue to spend a great deal of time in Dublin in the following decades. And it was also the city of Sean O’Casey and the site for the endeavours of Lady Gregory. The Abbey Theatre had been established by Gregory and Yeats in 1904. The culture of Dublin was diverse, not narrow.

The contested nature of culture in the capital was replicated in its politics. 1911 brought events which illustrated the breadth of its divisions. In July King George V spent six days in Dublin on a royal visit to the city. The King and the royal party, led by the 8th Royal Hussars on horseback, travelled from the harbour in Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) to Dublin Castle, as thousands lined the streets to view his procession.

But, also in 1911, a Wicklow-born Protestant who was originally a strong supporter of the British Empire, Robert Erskine Childers, published his treatise, The Framework of Home Rule, which advocated the restoration of a parliament to Dublin. Childers would later be shot by firing squad by Government forces during the civil war, fought over a treaty which he was unwilling to support.

By contrast, in September 1911, the unionist leader, Sir Edward Carson, born in Dublin and still an MP elected to the House of Commons by Trinity College, told an Orange Order meeting at Craigavon House: “We must be prepared … the morning Home Rule passes, ourselves to become responsible for the government of the Protestant province of Ulster.”

And finally, in October 1911, a large crowd turned up in Sackville Street (now O’Connell St.) to see a monument unveiled to the great nationalist politician, Charles Stewart Parnell. The monument was unveiled by John Redmond, leader of the Irish national party, and its inscription was plain in its independent intent:

“No man has a right to fix the

Boundary to the march of a nation.

No man has a right

To say to his country

Thus far shalt thou

Go and no further.”

In the ferment of its politics, the vibrancy of its culture, the vertical divide of its religions, and the extraordinary disparity in its wealth, Dublin bore all the hallmarks of a city on the edge of enormous change. And the dynamic behind that change was the 477,196 people who lived in the city of Dublin and its county hinterland.

Despite the wealth of the British empire and Dublin supposedly being the second city of it, the reality for the ordinary and average Dubliner was abject poverty. Dublin's slums were among the worst in the whole of Europe, and by far in the supposed united kingdom. This photograph, taken in 1913, shows tenement children on waste ground off Chancery Street. (RSAI, DD, No. 6)

In the city, many families were forced to put their children selling wares on the streets. A 1902 report dealing with the problem of the thousands of children street-selling, noted that in one in six cases, one or both parents were dead.

By 1911 the city slums also incorporated great Georgian houses on previously fashionable streets and squares. As the wealthy moved to the suburbs over the course of the 19th century, their huge, red-brick buildings were abandoned to the rent-paying poor. Tenements in inner-city Dublin were filthy, overcrowded, disease-ridden, teeming with malnourished children and very much at odds with the elite world of colonial and middle-class Dublin.

The decay of Dublin was epitomised by Henrietta Street, which had once been home to generations of lawyers, but was, by 1911, overflowing with poverty. An astonishing 835 people lived in 15 houses. At number 10 Henrietta Street, the Sisters of Charity ran a laundry with more than 50 single women inside. The other houses on the street were filled with families. For example, there were members of nineteen different families living in Number 7. Among the 104 people who shared the house were charwomen, domestic servants, labourers, porters, messengers, painters, carpenters, pensioners, a postman, a tailor, and a whole class of schoolchildren. Out the back were a stable and a piggery.

Browse the photo archive from 1911

Using Dublin 1911 census returns for genealogy

You can do a search online for people living in the city in 1911, enter the surname and as much information as you know of the person living in Dublin at the time.

Occupying a key position in the cultural and intellectual life of the nation, the National Archives holds the records of the modern Irish state which document its historical evolution and the creation of our national identity.

History of The National Archives

The National Archives, established on 1 June 1988, took over the functions previously performed by the State Paper Office (1702) and the Public Record Office of Ireland (1867).

Functions

The records acquired by the National Archives are referred to in the National Archives Act, 1986, as archives and the Act designates the functions of the National Archives with regard to archives in its custody as follows.

Legislation governing the National Archives

The National Archives is governed by a number of acts and regulations, the most important of which are listed below.

National Archives responsibility for archives

The National Archives annually receives thousands of documents relating to the business of Government.

Ministerial responsibility for archives

The National Archives Act, 1986 assigned ministerial responsibility for the National Archives to the Taoiseach.

National Archives Advisory Council

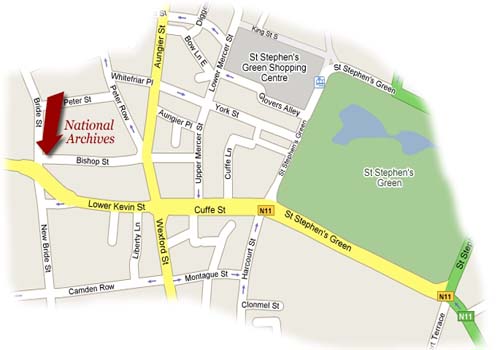

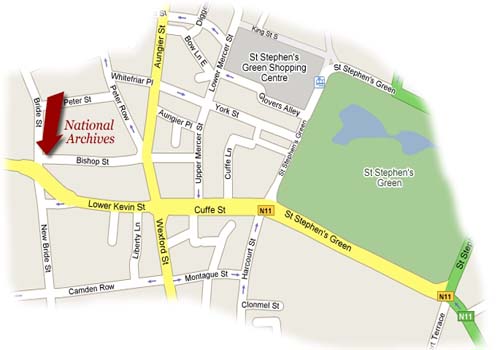

Location

The National Archives is located in Bishop Street, Dublin 8, close to the city centre and within ten minutes walk of St Stephen’s Green. No designated parking facilities are available on site but commercial multi-storey car parks are located nearby at St Stephen's Green and Christchurch Place.

Map indicating the location of the National Archives in Bishop Street, Dublin 8Map illustrating the location of the National Archives in Bishop Street, Dublin 8 - click on the thumbnail to enlarge or print

The National Archives Advisory Council was established in January 1987 under Section 20 of the National Archives Act, 1986, to advise the Minister with responsibility for the National Archives, the Minister for Arts, Sport and Tourism, in the exercise of his powers and on all matters affecting archives and their use by the public.

Publications

The National Archives and the Public Record Office of Ireland have published a number of reports, guides and manuals within the last three decades, for example, our Customer Charter and Freedom of Information Manual.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|